Nearly half of people diagnosed with advanced heart failure (HF) following a major heart attack die within five years. But research supported by GW4 Alliance funding could lead to earlier prediction and intervention – improving life expectancy.

Our research impact

Mixed Reality and AI to aid surgeons with keyhole heart valve surgery

Cardiac surgeons could in the future be conducting procedures virtually before even stepping into an operating theatre. A research team from UWE Bristol’s Big Data lab and Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences (HAS) is developing technology that uses artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to assist cardiac surgeons in planning and preparing for complex keyhole heart valve surgery.

The team is initially collaborating with the Bristol Heart Institute (BHI), a Specialist Research Institute at the University of Bristol, whose surgeons will test the system when preparing for minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery (MICVS).

Compared to conventional open-heart surgery involving cutting through the breastbone to reach the heart, MICVS is less intrusive as the heart is accessed through smaller incisions using endoscopic instruments. And patient recovery time is generally quicker after this keyhole surgery.

However, MICVS is complex and requires hours of pre-operative planning and preparation.

Dr Hunaid Vohra, Consultant Cardiac Surgeon and Honorary Senior Lecturer and Researcher at the BHI, who is collaborating with UWE Bristol, said:

“In the operating room, despite pre-planning, it is currently very common to find unexpected challenges, as every patient’s height, weight and heart-lung anatomy is different. And patients’ frailty varies.

“Mixed Reality and AI will enhance our ability to prevent the conversion of a keyhole heart valve operation to an open heart surgery, avoiding two sets of scars, and delay in recovery.”

Surgeons will initially be able to use the system’s AI to tap into the patient’s medical data to predict the risks associated with the procedure. The likelihood of adverse events is then presented to the surgeon on a HoloLens using AR.

Next, the surgeon will have access to AR technology to show a patient a 3D version of their heart and explain the procedure to them via headsets.

Dr Muhammad Bilal, Associate Professor of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence at UWE Bristol and leading the research team, said:

“Most terms surgeons use to describe heart surgery during consultation draw a blank from patients and this system makes the explanation task much clearer and easier.”

Incorporated in the system is also a pre-operative logistics element that optimises operation planning. This will assist medical teams in preparing the right instruments and materials, and booking the appropriate operating theatre and hospital beds, among other tasks.

Crucially, the software’s virtual planning feature will provide surgeons with access to a complete digital version of the patient, enabling them to perform the entire operation beforehand on a replica of the patient’s thoracic cavity. This will include ‘what-if’ scenarios to determine the most optimal and personalised surgical strategies.

Finally, in collaboration with UWE Bristol’s Centre for Print Research, surgeons performing very complex cases will be allowed to order a bespoke 3D printed model of the patient’s thoracic cavity mimicking organs, veins, and blood flow to simulate the procedure on a synthetic body.

Dr Vohra said:

“This will enable us to practise before the actual operation and minimise the potential for things to go wrong on the day. Overall, we are excited to be involved in this technology, which could spell the future for highly successful minimally invasive procedures of this type in adults and babies.”

Dr Bilal added:

“Currently, the practice of MICVS is limited to a small group of surgeons in the world. This technology-enabled guidance promises to increase the number of doctors able to perform these operations, providing wider access to the general population.

“There are significant engineering challenges to be resolved before this technology can be rolled out into the NHS but our collaboration with the BHI provides a perfect testing ground.”

TV watching linked with potentially fatal blood clots

Take breaks when binge-watching TV to avoid blood clots, say scientists. The warning comes as a study reports that watching TV for four hours a day or more is associated with a 35 per cent higher risk of blood clots compared with less than 2.5 hours. The University of Bristol research is published today in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, a journal of the ESC.

The study examined the association between TV viewing and venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE includes pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lungs) and deep vein thrombosis (blood clot in a deep vein, usually the legs, which can travel to the lungs and cause pulmonary embolism).

To conduct the study, the University of Bristol researchers conducted a systematic review to collect the available published evidence on the topic and then combined the results using a process called meta-analysis.

Lead author, Dr Setor Kunutsor from the University’s Bristol Medical School explained:

“Combining multiple studies in a meta-analysis provides a larger sample and makes the results more precise and reliable than the findings of an individual study.”

The analysis included three studies with a total of 131,421 participants aged 40 years and older without pre-existing VTE. The amount of time spent watching TV was assessed by questionnaire and participants were categorised as prolonged viewers (watching TV at least four hours per day) and never/seldom viewers (watching TV less than 2.5 hours per day).

The average duration of follow-up in the three studies ranged from 5.1 to 19.8 years. During this period, 964 participants developed VTE. The researchers analysed the relative risk of developing VTE in prolonged versus never/seldom TV watchers. They found that prolonged viewers were 1.35 times more likely to develop VTE compared to never/seldom viewers.

The association was independent of age, sex, body mass index (BMI) and physical activity. Dr Kunutsor said:

“All three studies adjusted for these factors since they are strongly related to the risk of VTE; for instance, older age, higher BMI and physical inactivity are linked with an increased risk of VTE.

“The findings indicate that regardless of physical activity, your BMI, how old you are and your gender, watching many hours of television is a risky activity with regards to developing blood clots.

“Our study findings also suggested that being physically active does not eliminate the increased risk of blood clots associated with prolonged TV watching,” said lead author Dr Kunutsor. “If you are going to binge on TV you need to take breaks. You can stand and stretch every 30 minutes or use a stationary bike. And avoid combining television with unhealthy snacking.”

Dr Kunutsor noted that the findings are based on observational studies and do not prove that extended TV watching causes blood clots.

Regarding the possible reasons for the observed relationship, he said:

“Prolonged TV viewing involves immobilisation which is a risk factor for VTE. This is why people are encouraged to move around after surgery or during a long-haul flight. In addition, when you sit in a cramped position for long periods, blood pools in your extremities rather than circulating and this can cause blood clots. Finally, binge-watchers tend to eat unhealthy snacks which may lead to obesity and high blood pressure which both raise the likelihood of blood clots.”

Dr Kunutsor concluded:

“Our results suggest that we should limit the time we spend in front of the television. Long periods of TV watching should be interspersed with movement to keep the circulation going. Generally speaking, if you sit a lot in your daily life – for example your work involves sitting for hours at a computer – be sure to get up and move around from time to time.”

Read the paper

Television viewing and venous thrombo-embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology by Setor Kunutsor, Richard Dey and Jari Laukkanen.

Further information

Authors’ note:

The findings are based on observational studies, so they do not prove cause and effect.

These findings are based on the results of only three studies. More studies are needed to confirm or refute the findings.

Pioneering stem cell therapy at Bristol Royal Hospital for Children

Dr Filippo Rapetto discusses an innovative case using donor stem cells which offers hope for babies born with heart problems.

Filippo, can you tell us what happened?

Filippo, can you tell us what happened?

Finley was four days old when he was diagnosed at Bristol Royal Hospital for Children with transposition of the great arteries, which affects about one in 3,000 newborns. The treatment, which is very well established, is an operation called arterial switch procedure, which includes a complex surgical step called coronary artery translocation. Unfortunately, in this case, one of the coronary arteries had an anomalous course and the translocation was not successful. This caused a significant deterioration in Finley’s cardiac function.

We struggled for a couple of months with various treatments, such as extra corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). After we managed to wean him off that, he was still in intensive care for many weeks, dependent on inotrope drugs to increase his heart function, which was very poor.

Because there was no conventional way to treat his condition, Professor Massimo Caputo with the Paediatric Cardiac Surgery team, the Paediatric Cardiology team and the Paediatric Intensive Care team, suggested we source donor mesenchymal stromal cells (stem cells) to inject directly into Finley’s heart with a second surgical procedure. We have a collaboration with the Centre for Cell, Gene and Tissue Therapeutics (Royal Free Hospital, UCL) which provided us with the cells within a few days. Professor Caputo managed to get compassionate funding from the Trust, and he got the process going quickly.

Following the procedure, we noticed a slow but consistent improvement in the patient’s clinical conditions. We then did multiple echocardiograms to monitor the cardiac function, and it got gradually and consistently better. He was able to go home about three months after the stem cell injection.

Has he made a full recovery?

He started from what we call a severe dysfunction and now his heart function is close to normal, comparable with someone who had a heart operation as a newborn.

What evidence do you have that the procedure worked?

From a scientific point of view, the only way to know whether this procedure helped would be to take some of the patient’s myocardium (muscular tissue of the heart) and analyse it, which clearly we cannot do, but the clinical change after the injection was impressive. This stem cell injection technique is not something that we invented, but this case is the first in the world that we know of, for this condition, at this age, in a patient with established cardiac dysfunction (rather than as a preventive measure), and with donor stem cells rather than previously collected cells from the patient.

How difficult is it to find a match from donor stem cells?

One of the criticisms made about this approach in the past is that there is a potential risk of triggering an immune response, but this has been shown not to be the case. No complex immunological matching is needed to utilise the cells, as they don’t necessarily have to survive in the patient for a long time. The hypothesis is that they promote the recovery of the patient’s own tissues by acting as modulators of the patient’s healing processes.

Once we took the decision to try this procedure, then everything happened pretty quickly, and that’s the beauty of it. Because he was getting worse, we didn’t have the possibility of isolating their own cells and making them grow to obtain a sufficient dose – he was too unwell.

Was there an alternative?

In desperate cases like this one, you could go to urgent transplantation, but it’s very difficult to find a heart for a newborn because there are very few donors. Also, this happened in the middle of the first lockdown, when the transplantation service had pretty much stopped all over the country, for nearly all patients, so this wasn’t an option.

Stem cell treatment is not the codified, recognised treatment, whereas transplantation is, so we had a discussion with several transplant centres. But I think the chances of finding a heart in time, and ultimately the chances of a good outcome, would have been minimal if we had waited longer.

What’s the next step in the research?

This case is important because it demonstrates that cells that are not autologous (that come from different individuals) are safe to use. There are a lot of patients with other congenital heart conditions that could potentially benefit from this concept, so this is extra evidence that stem cell therapy has potential.

Might this technique become a standard way of treating these kinds of conditions?

With Professor Caputo’s research group, we already use similar stem cells in our animal research projects, and we are trying to translate their use from animals to humans. There are several common congenital heart defects, which require some sort of surgical valve and/or vascular replacement with prosthetic materials, but these materials don’t grow or repopulate with the patient’s tissues. We want to reduce the rate of replacement, so we are trying to merge the currently available materials with stem cells to create a more biologically compatible tissue to be used in children.

We are delighted that Professor Caputo has been awarded a three-year BHF Translational Award to take this research to the next stage. If a subsequent clinical trial shows that the therapy is effective, this new treatment could potentially avoid repeated high risk and stressful heart operations, and significantly improve quality of life for many children living with congenital heart disease.

Read the case report

‘Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Injection to Alleviate Ischemic Heart Failure Following Arterial Switch Operation‘ by Filippo Rapetto, Demetris Taliotis, Qiang Chen, Iakovos Ttofi, Dominga Iacobazzi, Paolo Madeddu, Serban C. Stoica, Ben Weil, Mark W. Lowdell, and Massimo Caputo, in JACC: Case Reports

Research into new treatments for CHD boosted by funding awards

Two new grants will further BHI research into progeria and pulmonary hypertension:

MRC: Gene-inspired therapy to rescue cardiovascular disease in progeria: awarded to Professor Paolo Maddedu

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), characterised by a rapidly ageing appearance, is a rare disease caused by an abnormal gene and related protein. Because there is no effective cure, children with HGPS will, on average, die of cardiovascular disease at around 14 years old.

This project proposes a new treatment where a gene – found in people who live a long and healthy life – is transferred to rescue the premature cardiovascular senescence typical of HGPS patients.

Professor Paolo Madeddu’s team has discovered a beneficial variant of the BPIFB4 gene, and shown in animal models that transferring this gene reduces the suffering from a heart attack, diabetes and high blood pressure. Preliminary studies showed that the longevity BPIFB4 mutation can benefit some molecular mechanisms that are dysfunctional in children with HGPS.

Paolo says:

“We will determine the efficacy of BPIFB4 gene therapy in HGPS mice, looking at the treatment’s ability to preserve heart and blood vessel function. In addition, we will investigate the mechanisms underpinning this benefit, using human cells from HGPS patients. If results are positive, we will continue our research confirming the lack of toxicity, defining the best dose and timing of treatment for prolonged benefit and the advantage of adding BPIFB4 therapy to current drugs, in view of obtaining permission for a clinical study in patients.”

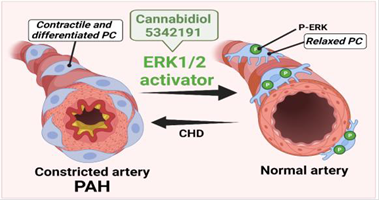

HRUK: Targeting pericytes for halting pulmonary hypertension in infants with CHD: awarded to Professor Paolo Madeddu, Professor Massimo Caputo and Dr Elisa Avolio

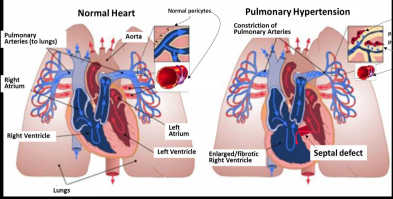

Some children are born with a ventricular septal defect: a hole in the wall between the two lower chambers of the heart, where blood can flow across the hole from the left side of the heart to the right. If the defect is not corrected in time, children are likely to develop pulmonary hypertension (high pressure in the blood circulation to the lung).

Surgical correction of the ventricular shunt usually allows the blood pressure in the lungs to return to normal levels. In some cases, however, the pressure may stay higher than normal after surgery.

At least five to 10 per cent of patients with congenital heart disease develop pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), which can lead to heart failure. The risk of developing pulmonary hypertension is higher for children living in poor countries and areas of social deprivation, because of the limited access to specialist centres where the cardiac defect can be recognised and corrected before complications arise.

Recent research indicates pericytes – multi-functional cells embedded within the walls of capillaries – could be targeted for the treatment of PAH. Paolo says:

“Our research will investigate why pericytes from children with CHD constrict and block the pulmonary circulation. It will also test a new treatment to reduce the contraction of pulmonary pericytes and prevent pulmonary hypertension occurring.”

Fostering collaboration and supporting early career researchers

Eighty Bristol Heart Institute researchers joined ‘Fostering collaboration and supporting early career researchers’, our 5th Annual Meeting on 19 November 2021. The day was an opportunity not only to get to know some of the research taking place in the University’s Specialist Research Institute, but also the researchers driving it forward.

BHI researcher talks

In the first session on cardiac surgery, Massimo Caputo looked at tissue engineering, combining surgical facilities and imaging technologies in ‘hybrid’ theatre, cardiac 3D printing to help plan operations and how advances in VR technology are taking this to the next level.

Next, Tom Johnson, Consultant Cardiologist and recently appointed Associate Professor, examined a range of cardiovascular research priorities, from intracoronary imaging to industry collaboration, AV Cath lab broadcasting to encourage collaboration and the potential for system-wide datasets to enhance patient outcomes.

Jules Hancox from the School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience shared some thoughts on career progression for early career researchers, including memorable advice about choosing a research project: “Interesting is not equivalent to important” – a trap that all researchers fall into from time to time, he acknowledged!

To wrap up the morning’s talks, Deborah Lawlor discussed Bristol’s epidemiological research in the BHI.

Plenary

For the plenary we welcomed Professor Andrew Taylor, Director of Innovation at Great Ormond Street Hospital and Head of Cardiovascular Imaging at UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Science, to talk about innovating in cardiovascular research. Using examples such as fast imaging protocols and the potential for delivering precision medicine via AI, he looked at why putting innovations into clinical practice at pace remains challenging, and how ongoing interaction between researchers and clinical teams is vital.

Quickfire presentations

BHI PhD students and early career researchers were invited to present their work in five minutes in three themed sessions covering epidemiology, basic science and clinical research. Attendees voted for the best presentation in each session – well done to:

- Lucy Goudswaard: “Combining Mendelian randomisation and randomised control trial study designs to determine effects of adiposity on the plasma proteome”

- Stanley Buffonge: “The battle to protect the coronary microvascular endothelial glycocalyx in diabetes”

- Monica Gamez: “Endothelial glycocalyx heparan sulfate contributes to the integrity of the blood-retina-barrier and can be therapeutically targeted in diabetes mellitus”

Thank you

Thanks to everyone who took part in the meeting and especially to the organising committee, without whom the day wouldn’t have been possible: Alexander Carpenter, Alba Fernandez-Sanles, Laura Pannell, Eva Sammut and Andrew Shearn, along with Giovanni Biglino and Stuart Mundell.

Laura says:

“It was a fantastic day showcasing research the BHI can be proud of, and will enable the development of collaborative relationships for many years to come!”

Funding boost for remote cardiac care appeal

Bristol & Weston Hospitals Charity (formerly Above and Beyond) has been awarded £57,000 from NHS Charities Together to support its appeal to provide at-home monitoring service for BHI patients with pacemakers.

Thousands of BHI patients have a cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) or pacemaker to help control or monitor irregular heartbeats. Having a CIED requires them to attend hospital as often as every six weeks to be checked.

However, COVID-19 restrictions have severely affected patients’ ability to attend their hospital appointments. The average age of a person with a CIED in the UK is 75 years old, which puts these patients in a high-risk group.

Over lockdown, the BHI identified technology that would allow CIED patients to be monitored remotely instead. By providing patients with home monitoring equipment that they place by their bed, staff could routinely assess patients and perform essential tests without the patient leaving their home.

Remote monitoring reduces mortality in these patients as it enables the CIED clinic to detect heart failure events at an early stage and intervene before the patient develops symptoms. This includes being able to detect Atrial Fibrillation, which is the leading cause of stroke in the UK.

Following a successful trial in a cohort of complex CIED patients, this year Bristol & Weston Hospitals Charity launched an appeal to provide remote monitoring technology for all CIED patients at the BHI. This will reduce both waiting times in the clinic and the number of hospital visits overall, while providing an even more effective level of service and care.

The NHS Charities Together award, announced in September, comes as part of a package of support for 10 different health projects that will benefit more than 100,000 people in Bristol and beyond, not only those with heart conditions. Find out more

Welcome to the BHI Newsletter Autumn 2021

Professor Andy Judge, Head of Section for Cardiovascular Surgery and Vascular Biology, reflects on recent successes.

With the new academic year underway, we welcome our new cohorts of postgraduate taught master’s degree students for the MSc in Perfusion Science and the MSc in Translational Cardiovascular Medicine (TCM). The teaching sessions are now back in person for the campus based TCM students and Perfusion students, and our student numbers are good.

I’m pleased to report that the labs, which closed for three months at the start of the pandemic, have been open since June 2020. Staff are gradually returning to the office at Level 7 of the BRI as the University has launched its blended working trial policy, and we are now seeing more staff in both the labs and offices.

Within our section for Cardiovascular Surgery and Vascular Biology at the University, we are delighted to have been able to appoint staff to new posts. Dr Kerry Wadey has been appointed as Lecturer in Cardiovascular Medicine on an open-ended core funded post. Francesco Paneni has been appointed as a Professor in Cardiology and Tom Johnson as an Associate Professor in Cardiology and they are expected to begin working with us at the start of 2022.

A number of staff in our section have had success following the annual University promotions procedure. Jason Johnson has been promoted to Professor of Cardiovascular Pathology, and Umberto Benedetto becomes Professor of Cardiac Surgery. Staff from the Teaching and

Learning for Health Professionals (TLHP) programme have recently joined our department of Translational Health Sciences and come under

the umbrella of our cardiovascular section, where we are delighted to congratulate Andrew Blythe on being promoted to Professor of Medical Education in this year’s annual promotion procedure.

Huge congratulations to all those recently promoted: we wish them continued success in their careers.

Bristol Heart Institute researchers feature in World Heart Day campaign

Four Bristol Heart Institute researchers have shared their work in a campaign to mark World Heart Day, 29 September 2021.

The interviews, which appear in the Guardian newspaper’s Cardiovascular Health supplement, cover a broad aspect of the BHI’s work, from tissue engineering to population health.

BHI Director, Professor Gianni Angelini, outlines the BHI’s innovative link between clinicians and scientists, citing the combination of people from different disciplines – basic scientists, clinicians, engineers, epidemiologists and statisticians – as one of the Institute’s key strengths.

Professor of Congenital Cardiac Surgery, Massimo Caputo, talks about how tissue engineering and stem cell therapies could lead to better treatment options for young patients with congenital heart disease.

Dr Giovanni Biglino, Senior Lecturer in Biostatistics, explains how patients and the public are playing an increasing role in cardiovascular research through closer collaborations with clinicians, researchers and artists. This is supporting clinical training and medical research as well as helping patients have a better understanding, and acceptance, of their heart conditions.

Finally, Deborah Lawlor, Professor of Epidemiology, talks about using population health data to identify causes of cardiovascular disease and to predict who is at risk of it. which can lead to prevention, early detection and effective treatment of disease.

Fat matters more than muscle for heart health, research finds

New research has found that changes in body fat impact early markers of heart health more than changes in body muscle, suggesting there are greater benefits to be expected from losing fat than from gaining muscle.

The observational study, led by researchers from the University of Bristol, was published today [9 September] in PLoS Medicine.

More than 3,200 young people in Bristol’s Children of the 90s birth cohort study were measured repeatedly for levels of body fat and lean mass using a body scanning device. These scans were performed four times across participants’ lives, when they were children, adolescents, and young adults (at ages 10, 13, 18 and 25 years). Handgrip strength was also tested when they were aged 12 and 25 years.

When the participants were 25 years old, blood samples were collected and a technique called “metabolomics” was used to measure over 200 detailed markers of metabolism including different types of harmful cholesterol, glucose, and inflammation, which together indicate one’s susceptibility to developing heart disease and other health conditions.

Dr Joshua Bell, senior research associate in epidemiology and lead author of the report, said:

“We knew that fat gain is harmful for health, but we didn’t know whether gaining muscle could really improve health and help prevent heart disease. We wanted to put those benefits in context.”

The findings showed that gaining fat mass was strongly and consistently related to poorer metabolic health in young adulthood, as indicated, for example, by higher levels of harmful cholesterol. These effects were much larger (often about 5-times larger) than any beneficial effect of gaining muscle. Where there were benefits of gaining muscle, these were specific to gains that had occurred in adolescence – suggesting that this early stage of life is a key window for promoting muscle gain and reaping its benefits.

Dr Bell added:

“Fat loss is difficult, but that does seem to be where the greatest health benefits lie. We need to double down on preventing fat gain and supporting people in losing fat and keeping it off.

“We absolutely still encourage exercise – there are many other health benefits and strength is a prize in itself. We may just need to temper expectations for what gaining muscle can really do for avoiding heart disease – fat gain is the real driver.”

The study also found that improving strength (based on handgrip) has slightly greater benefits for markers of heart health than gaining muscle itself, suggesting that the frequent use of muscle, rather than the bulking up of muscle, may matter more.

Professor Nic Timpson, the Principal Investigator of the Children of the 90s and one of the study’s authors, said:

“This research provides greater clarity in the relative roles of fat and lean mass in the basis of cardio-metabolic disease. This is an important finding and clearly part of a complex picture of health that involves weight gain, but also the other indirect costs and benefits of different types of lifestyle. It is only through detailed, longitudinal, studies like Children of the 90s that these relationships can be uncovered. We extend our thanks to the participants of the Children of the 90s who make all of this work possible.”

Read the paper

‘Body muscle gain and markers of cardiovascular disease susceptibility in young adulthood: A cohort study‘ by Joshua A. Bell, Kaitlin H. Wade, Linda M. O’Keeffe, David Carslake, Emma E. Vincent, Michael V. Holmes, Nicholas J. Timpson and George Davey Smith in PLoS Medicine

Further information

The research was funded by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research at the University of Bristol and the Wellcome Trust. The research was also supported by the UK Medical Research Council; Health Research Board of Ireland; Diabetes UK; World Cancer Research Fund; British Heart Foundation; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR); Cancer Research UK.

About Children of the 90s

Based at the University of Bristol, Children of the 90s, also known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), is a long-term health-research project that enrolled more than 14,000 pregnant women in 1991 and 1992. It has been following the health and development of the parents and their children in detail ever since and is currently recruiting the children and the siblings of the original children into the study. It receives core funding from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol. Find out more at www.childrenofthe90s.ac.uk.