New research has found that changes in body fat impact early markers of heart health more than changes in body muscle, suggesting there are greater benefits to be expected from losing fat than from gaining muscle.

The observational study, led by researchers from the University of Bristol, was published today [9 September] in PLoS Medicine.

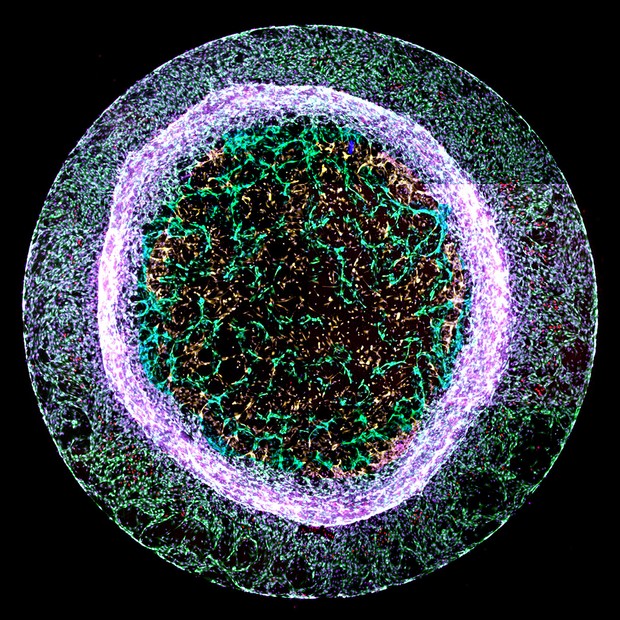

More than 3,200 young people in Bristol’s Children of the 90s birth cohort study were measured repeatedly for levels of body fat and lean mass using a body scanning device. These scans were performed four times across participants’ lives, when they were children, adolescents, and young adults (at ages 10, 13, 18 and 25 years). Handgrip strength was also tested when they were aged 12 and 25 years.

When the participants were 25 years old, blood samples were collected and a technique called “metabolomics” was used to measure over 200 detailed markers of metabolism including different types of harmful cholesterol, glucose, and inflammation, which together indicate one’s susceptibility to developing heart disease and other health conditions.

Dr Joshua Bell, senior research associate in epidemiology and lead author of the report, said:

“We knew that fat gain is harmful for health, but we didn’t know whether gaining muscle could really improve health and help prevent heart disease. We wanted to put those benefits in context.”

The findings showed that gaining fat mass was strongly and consistently related to poorer metabolic health in young adulthood, as indicated, for example, by higher levels of harmful cholesterol. These effects were much larger (often about 5-times larger) than any beneficial effect of gaining muscle. Where there were benefits of gaining muscle, these were specific to gains that had occurred in adolescence – suggesting that this early stage of life is a key window for promoting muscle gain and reaping its benefits.

Dr Bell added:

“Fat loss is difficult, but that does seem to be where the greatest health benefits lie. We need to double down on preventing fat gain and supporting people in losing fat and keeping it off.

“We absolutely still encourage exercise – there are many other health benefits and strength is a prize in itself. We may just need to temper expectations for what gaining muscle can really do for avoiding heart disease – fat gain is the real driver.”

The study also found that improving strength (based on handgrip) has slightly greater benefits for markers of heart health than gaining muscle itself, suggesting that the frequent use of muscle, rather than the bulking up of muscle, may matter more.

Professor Nic Timpson, the Principal Investigator of the Children of the 90s and one of the study’s authors, said:

“This research provides greater clarity in the relative roles of fat and lean mass in the basis of cardio-metabolic disease. This is an important finding and clearly part of a complex picture of health that involves weight gain, but also the other indirect costs and benefits of different types of lifestyle. It is only through detailed, longitudinal, studies like Children of the 90s that these relationships can be uncovered. We extend our thanks to the participants of the Children of the 90s who make all of this work possible.”

Read the paper

‘Body muscle gain and markers of cardiovascular disease susceptibility in young adulthood: A cohort study‘ by Joshua A. Bell, Kaitlin H. Wade, Linda M. O’Keeffe, David Carslake, Emma E. Vincent, Michael V. Holmes, Nicholas J. Timpson and George Davey Smith in PLoS Medicine

Further information

The research was funded by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research at the University of Bristol and the Wellcome Trust. The research was also supported by the UK Medical Research Council; Health Research Board of Ireland; Diabetes UK; World Cancer Research Fund; British Heart Foundation; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR); Cancer Research UK.

About Children of the 90s

Based at the University of Bristol, Children of the 90s, also known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), is a long-term health-research project that enrolled more than 14,000 pregnant women in 1991 and 1992. It has been following the health and development of the parents and their children in detail ever since and is currently recruiting the children and the siblings of the original children into the study. It receives core funding from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol. Find out more at www.childrenofthe90s.ac.uk.